Berenice Baker spoke to Dr Samuel Perlo-Freeman, head of SIPRI’s Military Expenditure and Arms Production Programme, to find out how global military spend is calculated and what these figures mean in terms of real-world government defence budgets.

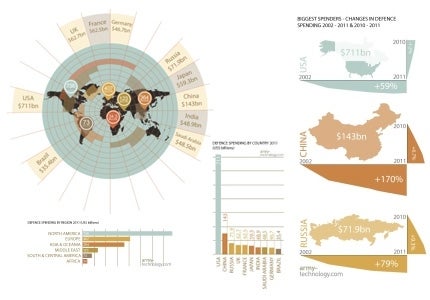

To find out more about global defence spending in 2011 and to read our infographic breakdown, click here.

Berenice Baker: How does SIPRI derive its figures?

Dr Samuel Perlo-Freeman: SIPRI has been collecting military expenditure data since the 1960s and we have been recording a consistent data series for each country from 1988 to 2011. We prioritise getting a consistent series over time for each country, so the trends can be meaningfully assessed in the data.

Within that constraint we try to get as close to our definition of military expenditure as we can, though that criterion is much harder to fill because so many countries will leave out significant items from the military expenditure figures they publish.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataWe use only open sources, or estimates based on open sources, which ultimately come from governments, or sometimes through secondary sources such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or Nato. We send out questionnaires to each country asking for aggregated military spending data, and we look at budget documents on the web, in print, in other financial reporting and official documents.

We then assemble all these sources for a given country and seek to construct series that are as consistent as possible, and then get as close as possible to our definition of military spending.

In some cases where we have expert budget analysts who send us their figures, or we produce detailed estimates for countries where there’s problems with transparency. When they are important countries, China for example, we make our own estimates based on a methodology developed by Professor Wang Shugang in 1999, which includes various items outside the official defence budget such as the People’s Armed Police paramilitary force and estimates for additional military R&D.

BB: Do you find it’s getting easier to get these figures, especially from more reluctant countries, as the SIRPI report becomes more well-known?

SP-F: In a lot of cases yes. In Europe we’ve had nearly complete data for a long time after the end of the Cold War, data from Eastern and Central Europe became much easier to come by. From Latin America we now have excellent data for because of increases in transparency and greater and more intensive efforts on behalf of our Latin American researcher.

The Middle East is very problematic. Iran stopped reporting after 2007 or 2008. In the UAE we have estimates based on IMF Staff Country Reports covering a particular set of years, so there’s no data for 2011, and they’re one of the region’s major spenders.

Africa is also very problematic for a lot of countries. It may be lack of transparency, or it may be partly a lack of capacity, so sources of data for a lot of those countries may be very intermittent. So you can see that for at least the most recent years there are a lot of countries for which the data is missing.

BB: Is there anything that particularly surprised you about this year’s figures?

SP-F: I wasn’t surprised that the total stopped growing. The signs were there that some regions were turning down while others were continuing to go up so it would probably be not huge an amount of change one way or another. I’m somewhat surprised by some of the downturns in Asia, in particular countries such as India and Vietnam, who have been increasing military spending quite a lot but saw a downturn just in 2011. This may just be a blip, but there are also some growing economic concerns in these countries that have seen very high rates of growth.

BB: Does the steady increase in Asia, while spending in the West is in general going down, reflect a shift in the balance of military power?

SP-F: It may eventually lead to a change in the balance of power, but I can’t see that happening in a significant way now.

The global balance of power is changing in various ways, economically, politically and diplomatically, with BRIC countries and countries such as Turkey becoming much more assertive diplomatically and wielding a more economic power.

But in terms of the military balance of power, the US is still so overwhelmingly ahead of everyone else, that I don’t see a real change in the balance of power coming. The US still spends five times as much as China, they’re the dominant power in the Pacific and around the world generally.

Geographically, countries such as China or India are in no position to project power into regions of direct concern to Europe, or indeed beyond their immediate regions, and are unlikely to be able to for some time to come, especially given the US dominance in the Pacific.

European countries such as Britain and France may become somewhat less able to project power or engage in major wars overseas, so it might become more difficult for the UK to do something [such as] the part they played in the Iraq invasion. However, in the main, US military power is likely to remain unchallengeable for quite a good time to come.

BB: Do you think part of India’s downturn in spending is down to a shift towards domestic production?

SP-F: China has already shifted towards domestic production, but that doesn’t necessarily make things cheaper. India’s aims have so far produced very limited results; SIPRI’s arms transfer figures show they’ve been the biggest arms importer over the past five years and are continuing to make very large deals.

Russia recently announced very large amounts of arms orders from India, and there are more in the pipeline, including negotiating with the French over the purchase of Rafale fighters. There’s no sign of a slowdown in arms purchases and the capital portion of the budget has especially been increasing in recent years.

One thing they well may be trying to do is get technology transfer from offsets as a by-product of their arms imports in the hope of boosting their domestic military technology, but it’s very early days in that process, and it would take a long time before that comes to fruition and allows them to build more advanced weapons domestically.

Even so, it doesn’t necessarily make it any cheaper if you’re newly developing your own technology compared to buying it off the shelf from countries that already have the technology. Very often, that’s actually more expensive.

BB: The report findings showed that the main areas which showed massive growth where North Africa and the Middle East. As the report refers to budgets that pre-date the Arab Spring, what do you put that down to?

SP-F: The increase in Africa is mainly due Algeria, which had an astonishing 44% increase which included increasing their defence budget mid-year by 22%. Some of that is down to enhancing security and equipment near the Libyan border due to spill-over from the conflict there.

But Algeria has been very rapidly increasing their military spending in general, fuelled by oil revenue. Although they’ve got the justification of combating Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, a lot of what they’re buying – naval equipment, plants, fighter aircraft – is not really suitable for counter-terrorism operations, it’s more about establishing themselves as a regional power.

For the Middle East more generally, there’s so little transparency in the region that it’s very hard to tell what the reasons behind increases are. The Iraq war certainly seem to have provoked general regional increases which have somewhat tailed off in the past few years. But these are generally increasing again, with tensions with Iran and rising oil prices for oil-producing states key factors.

BB: Europe’s spending has been going down quite rapidly among the countries affected by the economic downturn. Eastern Europe is still managing an increase. What do you put that down to?

SP-F: Some countries in Eastern Europe have been making cuts, and Russia even had a downward blip in 2010 as part of the after-effects of the crisis. But despite having had some significant economic problems – their GDP hasn’t fully recovered to what it was before the crisis – Russia is very much intent on modernising their armed forces. With their often Soviet-era equipment, the Georgian war gave them quite a nasty shock about some serious gaps.

They’re very keen to establish themselves as a regional power. You see not just their overall level of spending but their share of GDP devoted to the military generally trending upwards over the year. They’re planning further increases in the national defence budget – something like 53% in real terms in the next three years to 2014 – which is much faster than any likely GDP growth rate.

The other country that’s been increasing extremely rapidly is Azerbaijan. They had the largest single increase worldwide in 2011, of 88% in real terms. They have a lot of oil and they also have a long-running but currently dormant conflict with Armenia over the breakaway region of Nagorno-Karabakh in Azerbaijan, which is mainly ethnic Armenian.

Armenian forces control both that region and a significant swathe of Azerbaijan territory west of Azerbaijan as a corridor between Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia. Negotiations have got nowhere so far, despite a long-running peace process, and Azerbaijan has been threatening for some time that if there is no progress towards a diplomatic solution, then they will resort to war.