From accessing smartphones and bank accounts to travelling abroad, the use of devices and systems that scan our biometrics is now a regular occurrence. Often we give it little thought, particularly when it speeds up a process that we are undertaking and adds an enhanced level of security. There is, however, a darker side to biometric collection and the way in which gathered data could be used for social control by authoritarian governments.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been at the forefront of collecting biometric data and using new technologies that aid mass surveillance and oppression. Significant resources have been funnelled into modernising China’s security infrastructure to ensure it is more effective at monitoring CCP critics and suppressing freedom of expression, both in the digital sphere (internet activism) and in the real world (protest marches).

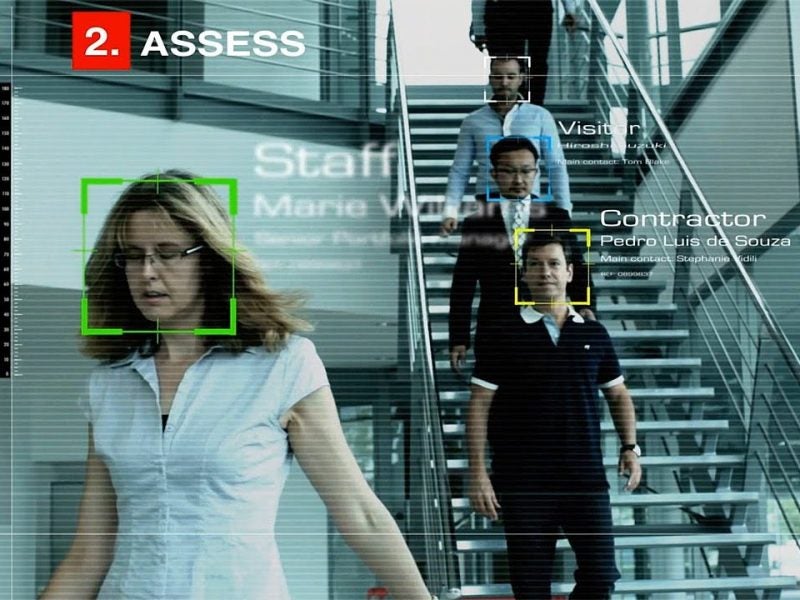

Overarching much of this has been the development and implementation of mass surveillance systems, including CCTV and schemes such as a national identification card that effectively tracks each citizen’s behaviours and activities. China is also at the forefront of systems that utilise big data and artificial intelligence algorithms, which collect and decipher the enormous amounts of data being generated by surveillance systems. This is enabling the identification of people from surveillance footage and also tracking behaviours to identify political dissent.

While this is occurring all across China, volatile regions such as Xinjiang in the northwest – which is home to several ethnic groups and has seen outbreaks of violence – are subject to even more extreme authoritarian measures underpinned by aggressive biometric collection and data analysis. Human Rights Watch (HRW) explained in a report released in May 2019 that under its ‘Strike Hard’ campaign, security services in Xinjiang had collected DNA samples, fingerprints, iris scans and blood types of all residents aged between 12 and 65, as well as voice samples for passport applications.

A dystopian present

“In Xinjiang, a region in China’s northwest, a new totalitarianism is emerging – one built not on state ownership of enterprises or property but on the state’s intrusive collection and analysis of information about the people there,” wrote Kenneth Roth, HRW’s long-running executive director.

While China is an extreme example, it is not surprising that many civil rights groups and technology experts are concerned about the expanding use of biometric surveillance tools in the west and the potential impact on individuals’ rights. Police forces across the UK – including in Wales and London – have trialled live facial recognition technology, with security services seeing this as a potential technical solution to under-resourced and overstretched police forces.

“The police in the United Kingdom have suffered under the policy of austerity that various governments have enacted since the financial crisis in 2008,” says Stephanie Hare, a researcher focused on technology, politics and history. “They have lost around 20,000 officers in the past decade, yet the pressures they are under are greater than ever: they must fight terrorism, a knife crime epidemic, and carry out their normal crime prevention and investigation duties. So it is understandable that the police will want to try different options to make better use of data and technology.”

She adds: “To do so effectively, they need to maintain the trust of the public, because good policing depends on this. That’s where their use of facial recognition is causing them trouble – research showing that facial recognition has a higher risk of misidentifying people with darker skins, women and children does not inspire confidence, but even if facial recognition were more accurate, there is the problem of it turning our public spaces into a dragnet, transforming us all into possible suspects who must prove our innocence, which violates a core tenet of a liberal democracy: we are innocent until proven guilty.”

Hare, who will publish a book on technology ethics later this year, believes that police use of biometric technologies requires “urgent parliamentary consideration” because the police have the power, under certain circumstances, to deprive citizens of our civil liberties and to use violence on behalf of the state.

Calls for a ban on facial recognition

Human rights organisation Big Brother Watch has called for an outright ban on live facial recognition technologies, which director Silkie Carlo says is now also being used increasingly by private companies at large shopping centres in the UK. “In all of these cases, we don’t know how long it has been going on, what watch lists are being used, what companies are watching us, or where our biometric data goes. The level of secrecy is unprecedented,” she wrote in August.

Concern about the private sector’s use of biometric technologies for security and surveillance is also echoed by Hare.

“The private sector use of biometrics technologies also requires parliament’s attention urgently because companies also have a lot of power over our lives and increasingly so thanks to the ability to connect disparate sources of data about us,” she says.

“Once they can link all that to our identity, as verified by our biometrics, we are in a whole new world of private sector surveillance – which the government will no doubt use. We will likely see a greater complicity between public and private sector organisations as they maintain and share watch lists and link it to all the other data about us either for security surveillance or for profit-driven surveillance.”

In June 2018, the UK’s Home Office released a long-awaited Biometrics Strategy that aimed to establish an overarching framework for how biometric data is collected and used, as well as how to increase public confidence in such systems. The 27-page document was met with criticism, with UK lawmaker Norman Lamb, the chair of the Science and Technology Committee, noting that it “in no way did justice to the fundamental issues involved, particularly around loss of privacy”.

In July, Lamb added to this, saying: “The legal basis for automatic facial recognition has been called into question, yet the government has not accepted that there’s a problem. It must. A legislative framework on the use of these technologies is urgently needed. Current [live facial recognition] trials should be stopped and no further trials should take place until the right legal framework is in place.”

Hare says the government should, firstly, have a moratorium on facial recognition and all other biometrics technologies, except those which are already covered under UK law (DNA and fingerprints).

“Second, the government should hold a consultation period in parliament where experts are invited to give evidence, the public is invited to give opinions, and parliamentarians and legal experts consider what role, if any, we want biometrics and surveillance technologies to play in British life. If we do want to use them, then under what conditions and with what oversight?”