Little more than five years ago, biometric technology still largely represented a new and somewhat unconventional item in the military toolkit – an "add-on to the mission," in the words of Myra S Gray, director of the US Army’s Biometrics Identity Management Agency (BIMA).

Today, with estimates suggesting that information about 2.2 million Iraqis and 1.5 million Afghans – said to roughly equate to a quarter and one in six of all the men of fighting age in their respective populations – is held on Nato and local national databases, that perception has undoubtedly changed.

While conventional photographs and fingerprints have been widely relied upon to establish individual IDs for decades, the principal advantage biometrics brings is the ability to search millions of files in seconds. This, coupled with its ability to provide accurate identification at even the most remote of locations via portable, hand-held devices, as well as swiftly scan databases held by a range of different agencies as appropriate, has cemented the technology’s position as an integral part of modern military operations.

That proven value has helped fuel the kind of interest that has seen the global biometric market tipped to achieve a compound annual growth rate of around 23% over 2011-2013, according to market research consultants RNCOS.

Establishing ID

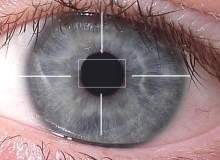

Given the nature of conflicts facing the modern soldier, speed and certainty are essential when it comes to distinguishing friend from foe, and in this context, iris recognition is one of the most widely familiar biometric tools – and the one which has probably enjoyed the most attention to date.

Combining computer imaging, recognition algorithms and statistical inference to mathematically analyse the complex, unique patterns of an individual’s eyes – typically comparing 200 or more sample points – this technology is said to be at least as accurate as a single fingerprint and can provide certain real-time identification in the field.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataThe key to it lies in the fact that iris structure is set during early development, while it remains remarkably stable throughout life. The upshot of this is that in the absence of a person suffering significant eye damage, a ‘one-off’, single digitised image can provide a lifetime of unambiguous ID – largely regardless of any interference from spectacles or contact lenses.

DNA too offers identification on an unchangeable basis, but despite its renowned forensic value, it is often less appropriate for many in-theatre military applications. As consultant biochemist Dr Clare Miles explains time can be a serious limiting factor. "Although it allows you to get an ID with unprecedented accuracy, and even though the technology has improved enormously over recent years, it’s still not what you’d exactly call a five-minute job."

Real-time biometric identification by means of DNA analysis has, however, recently come a step closer with the announcement at the end of 2011 of a contract for Northrop Grumman Corporation and teammate IntegenX Inc to supply the latter’s RapidHIT 200 human DNA identification system to the US Army’s BIMA.

This system – the first ever, fully automated approach, capable of producing standardised DNA profiles from routine cheek swabs and other samples in less than 90 minutes – means analysis can now take place at the point of collection, avoiding the usual delays as samples are transported to distant laboratories for processing. It may still not quite be a ‘five-minute job’, but it undeniably raises the bar on actionable DNA biometrics.

Successes and limitations

There have already been some notable successes – perhaps most significantly with the role biometric profiling played in April 2011 in helping to recapture 35 escapees within days of a Taliban devised break out from Kandahar’s Sarposa Prison.

With their iris scans, fingerprints and facial data recorded on the US Automated Biometric Information System database, many were caught at routine checkpoints, while one was arrested at a recruiting station attempting to infiltrate Afghan security forces.

Nevertheless, current technology has its limitations. In the aftermath of the Sarposa jail-break, for instance, many hand-held devices were found to be suffering from what were officially described as functioning ‘issues’ in the heat.

There are other factors too, as even the most robust of screens can break if dropped, and more widely, the roll out of all forms of biometric identification for unsupervised applications, such as entry points, is hampered by the obvious need to ensure the body part presented is still attached to its rightful owner.

Clearly there are challenges for the future, but the technologies are fast evolving to meet them.

New directions

One of the potentially most game-changing applications mooted, one which is currently in development, would see military personnel able to capture iris and facial scans of individuals from a distance – effectively forming the logical convergence of surveillance with biometrics.

While this obviously removes the need to expose a soldier to possible danger to collect data, there is the further advantage that such covertly gathered biometrics allows a suspect to be entered on a database without that subject’s knowledge – which could represent a significant potential edge in the cat-and-mouse game of counter-insurgency.

Honeywell’s prototype Combined Face and Iris Recognition System (CFAIRS), for instance, is intended to be able capture biometric information and track an individual on the basis of it, from up to four metres. Although currently only in the testing phase, reports suggest it is capable of achieving around 95% accuracy.

Similar research is underway too at Carnegie-Mellon University, where a BIMA-funded programme is developing a vehicle-mounted camera system to capture scans automatically at a distance of 12 metres. Add to this some of the newly-emerging techniques of ‘soft-biometrics’ to identify ethnicity from iris texture, which it is claimed is up to 90% accurate, and researchers believe practical military applications of these systems will not be far in the future.

Automating future conflicts

In the longer term, it could also open up the way for what has become known as ‘tactical non-cooperative biometrics’ – using biometric data as a means to target the enemy.

The move towards increasing automation is already apparent, and with many of the world’s defence budgets squeezed, the appeal of collecting biometrics via surveillance and drones, which can then be used to fight some kind of highly-robotic future war is clear – despite its distinctly sci-fi overtones.

However, as Major Mark Swiatek of the US Air Force Academy pointed out at September’s Biometric Consortium Conference in Florida, the idea of allowing "boxes" to "do all the dirty work" raises a whole host of difficult questions, ethically, politically and practically. Automated systems need programming, and that requires intent.

For the moment at least, away from the battlefield, the military applications of biometrics appear set on a less contentious course. According to Gray, "the next big step forward in biometrics is definitely going to be in the business process arena", where she suggests it can help the US Army improve efficiency and reduce fraud.

In the month that President Obama announced arguably the most significant defence review in American military history, with a 15% reduction to the US Army and Marine Corps on the cards, that seems to be a good direction in which to be headed.